It’s the damnedest thing.

I don’t know what it is

about this line of inquiry, but this series of posts has garnered more clicks –

and even Facebook shares – than anything else I’ve written. As far as I can

tell, though, this will be the last entry for now on the topic. (We’ll see what

happens in about 800 words when I realize I still have more to say and don’t

want to strain your patience.)

Let me deal with the Arthur Miller reference I made in the last colyum. I need to preface that, though, with some background on Sydney’s Belvoir Street Theatre.

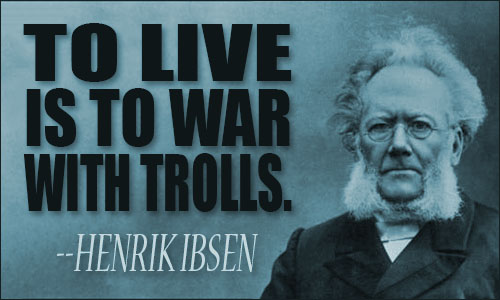

If I won't link to it, I should at least show it.

Looking at their website, it

seems like they’re a company dedicated to screwing around with other people’s creations

while relentlessly patting themselves on the back for doing so. Consider this

blurb for “Miss Julie:” “August Strindberg’s masterpiece has been hovering in

the wings at Belvoir for a while now, waiting for the right people: Leticia

Cáceres and Brendan Cowell both know how to combine tender and brutal to

devastating effect. Simon Stone joins them with a rewrite of the play in the

fashion of his The Wild Duck.”

Note the “his” there, which refers to Mr. Stone, and not either the late Mr.

Strindberg or the late Mr. Ibsen. Pretty much every description of the plays

they produce refers to an “adaptation” of this or “a contemporary version” of that.

Not content to adhere to the intentions of the playwright, they’ve decided that

their only responsibility is to themselves.

Mind you, I'm not saying this would be Ibsen's opinion of Stone, but ...

Not only did he cut the play's

epilogue, but he altered the manner in which Willy Loman, Arthur Miller's

protagonist, meets his death. In the original play, Willy dies in a car crash

that may or may not have been intentional; in Mr. Stone's staging, he commits

suicide by gassing himself. On top of that, Belvoir neglected to inform ICM

Partners, the agency that represents Mr. Miller's estate and licenses his plays

for production around the world, that Mr. Stone was altering the script.

Since rewriting dead

playwrights seems to be Stone’s stock in trade, I can see why he didn’t feel

the author’s representatives were worth notifying. I’m actually surprised he

was did something as boring, traditional, and mundane as casting a male actor

as Willy. They’re currently doing “Hedda Gabler” (a play that’s dismal enough) with

a male actor playing Hedda. Because A) it’s supposed to make a statement about

gender roles and B) apparently there aren’t any women in Sydney who are capable

of playing the part.

Hedda Gabler, ladies and gents.

Mr. Stone’s defense of his

bastardized presentation of Miller’s play was “"Until recently we accepted

the Broadway or West End way of treating their classics, now we are bringing to

them an Australian sensibility and technique. The world is responding."

Since the “Australian sensibility and technique” seems to involve violating

copyright and ignoring a writer’s intentions, it’s no wonder the world is “responding” – mainly by refusing him the rights to do anything. A look at their current season

shows rewrites of “Oedipus” (two of them!), “The Inspector General” (“inspired

by Nikolai Gogol” – who only wrote the goddamn thing), “Nora,” (“after ‘A Doll’s

House’ by Henrik Ibsen”), “A Christmas Carol” (“after Charles Dickens”) and “Cinderella.”

They’re also doing “The Glass Menagerie,” but I’d imagine the rights-holders

are keeping a close watch on them.

This kind of conduct goes to

the heart of how the Facebook discussion about the Mamet case went. The

opinions ranged from the conviction that the writer owns his or her words and

has every right to determine how they’re presented to an audience, to a belief

that since plays are more intangible things than physical, they should the property

of any director or actor who wanted to do anything they wanted with them. One

poster tried to make his case by saying that if I bought a shirt, he was free

to do whatever he wanted with it: cut off the sleeves, dye it, or whatever.

Never mind that he’s not buying that particular shirt; he’s borrowing it from

someone who probably won’t appreciate the alterations.

"Here's your shirt back -- or at least all the pieces."

I think I’ve made it pretty

clear which camp I fall into (the former, in case there was any doubt), but I

can almost see the point of the latter – IF (and it’s a big “if”) they’ve

talked to the creator of the work they want to tag with their graffiti. In my

experience, most writers are willing to at least listen to a director or

producer who has an innovative idea on how to recreate their work. They may not

agree to the changes, but they’ll listen. But if they say no; that’s it. If you

want to innovate, create your own work and do with it what you will.

We

Get Letters:

Eric L. writes: “How do you

think this incident compares to the Beckett's objection and legal action

against Akalaitis's production of Endgame?”

Thanks for asking, Eric. As

expected, though, I’ve reached my daily limit and will return to this topic

next time.

Is that Hedley Gabler, cousin of Hedley Lamarr?

ReplyDeleteThat's Hedy!

ReplyDelete